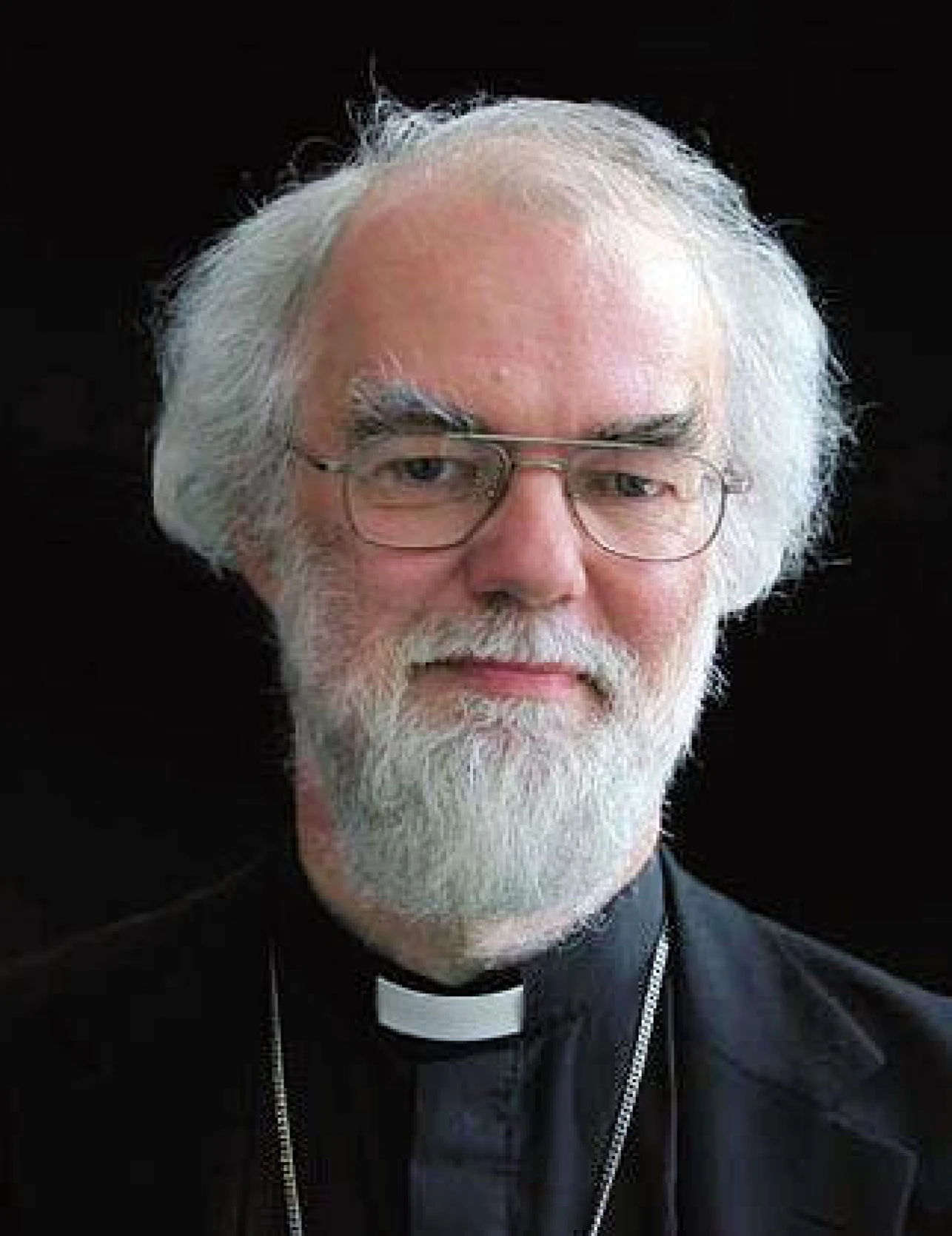

The Archbishop of Canterbury's Christmas Sermon

In his traditional Christmas sermon, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, focuses on how the birth of Jesus is but one stage of the fulfilment of God's unchanging promise of support in the struggle for human redemption, how 'the story of Jesus is the story of a God who keeps promises'.

So Christmas is a time of coming to terms with God's all embracing and redemptive love for us, despite the cost and the tragedy involved, the

human failures and betrayals. God, he asserts, despite our limitations and the humiliation our weaknesses lay on him, realises " we cannot live

without him; and he accepts everything for the sake of our well-being"

In this Christmas context, Dr Williams urges us to first of all contemplate our mutual dependence on our fellow human beings - our need for a spirit of fellowship and loyalty to each other in sharing the burdens of adversity in difficult economic times:

"Faced with the hardship that quite clearly lies ahead for so many in the wake of financial crisis and public spending cuts, how far are we able to sustain a living sense of loyalty to each other, a real willingness to bear the load together? How eager are we to find some spot where we feel safe from the pressures that are crippling and terrifying others? As has more than once been said, we can and will as a society bear hardship if we are confident that it is being fairly shared; and we shall have that confidence only if there are signs that everyone is committed to their neighbour, that no-one is just forgotten, that no interest group or pressure group is able to opt out."

And he points to the need for us to work positively together in order to rebuild trust:

"That confidence isn't in huge supply at the moment, given the massive crises of trust that have shaken us all in the last couple of years and the lasting sense that the most prosperous have yet to shoulder their load. If we are ready, if we are all ready, to meet the challenge represented by the language of the 'big society', we may yet restore some mutual trust. It's no use being cynical about this; whatever we call the enterprise, the challenge is the same - creating confidence by sharing the burden of constructive work together."

In the same way, the Archbishop also urges us to embrace the meaning of the forthcoming royal wedding, to recognise the significance of the Christian bond of marriage as a symbol of hope for humanity:

"Next year, we shall be joining in the celebration of what we hope will be a profoundly joyful event in the royal wedding. It is certainly cause for celebration that any couple, let alone this particular couple, should want to embark on the adventure of Christian marriage, because any and every Christian marriage is a sign of hope, since it is a sign and sacrament of God's own committed love. And it would be good to think that I this coming year, we, as a society, might want to think through,

carefully and imaginatively, why lifelong faithfulness and the mutual surrender of selfishness are such great gifts."

And in comparing Christian marriage with our covenantal relationship with God, the Archbishop reflects on - not only the trials of marriage - but also the inspirational examples of some marriages which he has seen:

"There will be times when we may feel stupid or helpless; when we don't feel we have the energy or resource to forgive and rebuild after a crisis or a quarrel; when we don't want our freedom limited by the commitments we've made to someone else. Yet many of us will know marriages where something extraordinary has happened because of the persistence of one of the parties, or where faithfulness has survived the tests of severe illness or disability or trauma. I admit, find

myself deeply moved at times when I speak with the families of servicemen and women, where this sense of solidarity is often so deeply marked, so generous and costly. As the prince and his fiance get ready for their new step into solidarity together, they will have plenty of inspiration around, more than you might sometimes guess from the chatter of our culture.

And finally Dr Williams asks us to remember during this time of Christian celebration our brothers and sisters in many lands who suffer repression and persecution for their Christian faith:

"I remind you of our Zimbabwean friends, still suffering harassment, beatings and arrests, legal pressures and lockouts from their churches; of the dwindling Christian population in Iraq, facing more and more extreme violence from fanatics - and it is a great grace that both Christians and Muslims in this country have joined in expressing their solidarity with this beleaguered minority. Our prayers continue for Asia Bib in Pakistan and others from minority groups who suffer from the

abuse of the law by certain groups there. We may feel powerless to help; yet we should also know that people in such circumstances are strengthened simply by knowing they have not been forgotten. And if we find we have time to spare for joining in letter-writing campaigns for all prisoners of conscience, Amnesty International and Christian Solidarity worldwide will have plenty of opportunities for us to make use of."

The full Christmas sermon text is below:

'This was to fulfill what the Lord had spoken through the prophet'.

Phrases like this echo like a refrain through the nativity stories in

the Gospels - and indeed the stories of Jesus' trial and death as well.

The stories of Jesus' birth and death were, from the very first, stories

about how God had kept his promise. The earliest Christians looked at

the records and memories of what had happened in and around the life of

Jesus and felt a sense of déjà vu: doesn't this remind you of...? Surely

this is the same as...?

Bit by bit, they connected up the details of the stories with a rich

pattern of events and images and ideas in Hebrew Scripture. Utterly

unexpected pregnancies - like Abraham's wife Sarah, or Hannah, mother of

the prophet Samuel. A birth in Bethlehem, where Jacob's wife died in

bringing to birth the last of the ancestors of Israel, where an

impoverished young widow from an enemy country was welcomed and made at

home, to become the grandmother of the great hero King David. Shepherds

in the fields of Bethlehem where young David had looked after his

father's flock before being called to be shepherd of the whole kingdom.

A star like the one foreseen by the ancient prophet Balaam as a sign of

Israel's victory; foreigners bringing gifts of gold and incense, as the

psalm describes foreign potentates bringing tribute to King Solomon . A

murderous attack on the children of God's people by a Godless tyrant, a

desperate flight and an exile in Egypt. The plain event at the centre of

it all, the birth of a child in a jobbing handyman's family, is

surrounded with so many echoes and allusions that it seems like the

climax of an immense series of great happenings; like the final

statement in a musical work of some theme that has been coming through

again and again, more and more strongly, in the earlier bars. The last

triumphant movement in God's symphony.

The story of Jesus is the story of a God who keeps promises. As St Paul

wrote to the Corinthians, 'however many the promises God made, the Yes

to them all is in him'. God shows himself to be the same God he always

was. He brings hope out of hopelessness - out of the barrenness of

unhappy childless women like Sarah and Hannah. He takes strangers and

makes them at home; he brings his greatest gifts out of those moments

when the barriers are down between insiders and outsiders. He draws

people from the ends of the earth to wonder - not this time at the glory

of Solomon but at the miracle of his presence among the humble and

outcast. He identifies with those, especially children, who are the

innocent and helpless victims of insane pride and fear. He walks into

exile with those he loves and leads them home again.

This is the God he has shown himself to be; and he has promised that he

will go on being the same God. 'I am who I am' he tells us; and 'I, the

Lord, do not change', and 'I will not fail you or forsake you.' When we

are faithless, he is faithful; when we seek to escape or even to betray,

he does not change. In what is perhaps the most unforgettable image in

the whole of Hebrew Scripture, God says that he has 'branded' or

'engraved' us on the palms of his hands (Is.49.16). He has determined

that he will not be who he is without us. And in this moment of climax

and fulfillment, in this last movement of the symphony, he shows in the

most decisive way possible that he will not be without us; he binds his

divine life to human nature. Never again can he be spoken of except in

connection with this human life that begins in the stable at Bethlehem.

>From one point of view, then, a story of triumphant persistence. Nothing

has shaken God's decision to be with those he has loved and called, and

now nothing ever will. Nothing, as St Paul again says, can separate us

from what is laid bare in the life and death and resurrection of Jesus.

And yet from another point of view, it is a story of unimaginable cost

and apparent tragedy. For if God has chosen to be with us in this way,

he is associated with our weaknesses, humiliated by our betrayals,

exposed and vulnerable to our casual decisions to take our custom

elsewhere. In the book of the prophet Hosea, we see this depicted in

harrowing terms as the marriage of a faithful man to an unfaithful

woman, a marriage which the man refuses to accept is over. I suspect

that a good many of us have seen cases of a faithful woman sticking

obstinately to an unfaithful man. In human terms, such faithfulness is

likely to look naïve, foolish or just pointless self-punishing. But God,

it seems, knows that whatever limitation and humiliation our human

freedom lays on him, we cannot live without him; and he accepts

everything for the sake of our well-being.

Christmas is about the unshakeable solidarity of God's love with us, not

only in our suffering but in our rebellion and betrayal as well. One

mediaeval Greek theologian, deliberately out to shock, described as

God's 'manic passion', God's 'obsession'; manike eros. And so it is a

time to do some stocktaking about our own solidarity and fidelity, our

own promise-keeping.

There are at least three things we might ponder in that respect, seeking

to understand ourselves better in the light of the Christmas story. The

first is our solidarity with one another, in our society and our world,

our solidarity with and loyalty to our fellow-citizens and fellow-human

beings. Faced with the hardship that quite clearly lies ahead for so

many in the wake of financial crisis and public spending cuts, how far

are we able to sustain a living sense of loyalty to each other, a real

willingness to bear the load together? How eager are we to find some

spot where we feel safe from the pressures that are crippling and

terrifying others? As has more than once been said, we can and will as a

society bear hardship if we are confident that it is being fairly

shared; and we shall have that confidence only if there are signs that

everyone is committed to their neighbour, that no-one is just forgotten,

that no interest group or pressure group is able to opt out. That

confidence isn't in huge supply at the moment, given the massive crises

of trust that have shaken us all in the last couple of years and the

lasting sense that the most prosperous have yet to shoulder their load.

If we are ready, if we are all ready, to meet the challenge represented

by the language of the 'big society', we may yet restore some mutual

trust. It's no use being cynical about this; whatever we call the

enterprise, the challenge is the same - creating confidence by sharing

the burden of constructive work together.

The second is something quite different, but no less challenging. Next

year, we shall be joining in the celebration of what we hope will be a

profoundly joyful event in the royal wedding. It is certainly cause for

celebration that any couple, let alone this particular couple, should

want to embark on the adventure of Christian marriage, because any and

every Christian marriage is a sign of hope, since it is a sign and

sacrament of God's own committed love. And it would be good to think

that I this coming year, we, as a society, might want to think through,

carefully and imaginatively, why lifelong faithfulness and the mutual

surrender of selfishness are such great gifts. If we approach this in

the light of what we have just been reflecting on in terms of the

Christmas story of a promise-keeping God, we shall have no illusions

about how easy it is to sustain such long-term fidelity and solidarity.

There will be times when we may feel stupid or helpless; when we don't

feel we have the energy or resource to forgive and rebuild after a

crisis or a quarrel; when we don't want our freedom limited by the

commitments we've made to someone else. Yet many of us will know

marriages where something extraordinary has happened because of the

persistence of one of the parties, or where faithfulness has survived

the tests of severe illness or disability or trauma. I admit, find

myself deeply moved at times when I speak with the families of

servicemen and women, where this sense of solidarity is often so deeply

marked, so generous and costly. As the prince and his fiancée get ready

for their new step into solidarity together, they will have plenty of

inspiration around, more than you might sometimes guess from the chatter

of our culture. And we can all share the recognition that, without the

inspiration of this kind of commitment in marriage, our humanity would

be a lot duller and more shallow - and, for the believer, a lot less

transparent to the nature of the God who keeps his covenant.

And lastly, a point that we rightly return to on every great Christian

festival, there is our solidarity with those of our brothers and sisters

elsewhere in the world who are suffering for their Christian faith or

their witness to justice or both. Yet again, I remind you of our

Zimbabwean friends, still suffering harassment, beatings and arrests,

legal pressures and lockouts from their churches; of the dwindling

Christian population in Iraq, facing more and more extreme violence from

fanatics - and it is a great grace that both Christians and Muslims in

this country have joined in expressing their solidarity with this

beleaguered minority. Our prayers continue for Asia Bibi in Pakistan and

others from minority groups who suffer from the abuse of the law by

certain groups there. We may feel powerless to help; yet we should also

know that people in such circumstances are strengthened simply by

knowing they have not been forgotten. And if we find we have time to

spare for joining in letter-writing campaigns for all prisoners of

conscience, Amnesty International and Christian Solidarity worldwide

will have plenty of opportunities for us to make use of.

Economic justice and Christian marriage and solidarity with the

persecuted - very diverse causes, you might think. But in each case, the

key point is about keeping faith, sharing risks, recognising that our

lives belong together. And all this is rooted for us in that event in

which all God's purposes, all God's actions, what we might call all

God's 'habits of behaviour' with us come into the clearest focus. 'This

was to fulfill what the Lord had spoken'; this was the 'Yes' to all the

promises. And what God showed himself to be in Hebrew Scripture, what he

showed himself to be in the life and death of the Lord Jesus, this is

what he ahs promised to be today and tomorrow and for ever. He cannot

betray his own nature, and so he cannot betray us. And by the gift of

the Spirit, we are given strength, in all these contexts we have

considered and many more, to let his faithful love flow through us, for

the fulfillment of more and more human lives according to his eternal

purpose and unshakeable love.