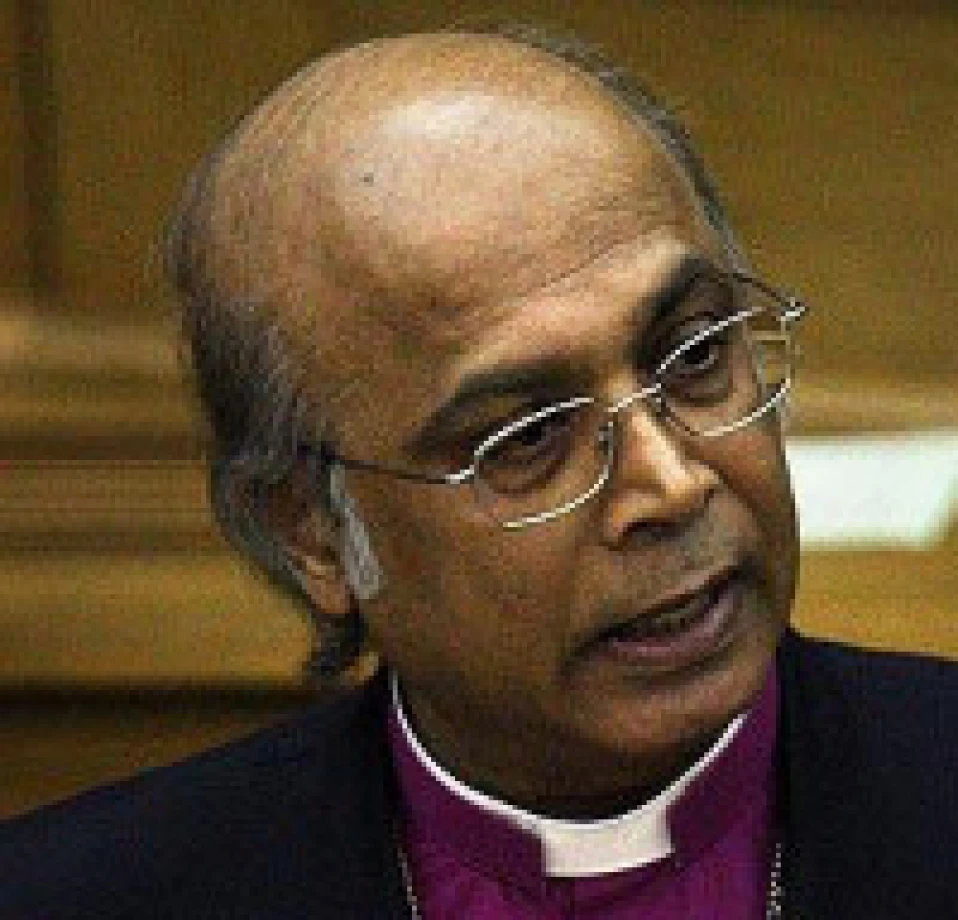

Christian values should take centre stage in public life says Bishop Nazir–Ali

In a message to David Cameron, Bishop Michael Nazir–Ali is calling for a new centrality for Christian values in public life. Welcoming the Prime Minister’s recent speech affirming the crucial role of Christianity as ‘music to my ears’ Bishop Michael considers how this should bear on policy–making in the coming months.

He is calling for:

The Judeao–Christian tradition to remain central to public life

A concerted programme to improve religious literacy in the Civil Service, Parliament and local authorities

A fresh recognition of the place of Christianity in the teaching of British history

The appointment of a new government advisory body on the moral and social implications of bioethics

Respect for conscience in the workplace in matters of controversy

Respect for the values of churches and Christian agencies participating in Big Society

The text of his article is the Sunday Telegraph is given below:

David Cameron must allow the Church to maintain a central role in public life by Bishop Michael Nazir–Ali

By any standards, the Prime Minister faces a very tough year: the economic crisis will continue and ordinary people will increasingly feel the weight of it. Whilst educational reforms will bring much needed change, they will be resisted by vested interests. Marriage and family life are crying out for much–needed support, but will it be provided? Moral renewal in the business world is urgent. A sense of vocation, responsibility and trust should be restored but, again, there will be those who have prospered with a ‘greed is good’ philosophy and who do not wish to see any change.

On both domestic and international fronts, the government faces the challenge of affirming democracy as well as the rule of law, whilst respecting freedom of expression and conscience. To what extent is it right for politicians to bring moral and spiritual consideration to the task of policy–making and of legislation, and what resources do they have in doing so?

In his recent landmark speech on the place of the Bible and Christianity in our national life, the Prime Minister not only noted the crucial rôle of the Bible in the development of English as a language and in areas such as art and literature but he also pointed out its importance for the morals and values which have made Britain what it is and their continuing significance today. This is very welcome but the question that is being asked is whether and how this is to bear on policy–making and legislation in the weeks and months to come?

He showed also how the political development of the nation is inextricably bound up with Christian ideas and values. According to him, constitutional monarchy, adult franchise, the rule of law and the equality of all before the law, have clear biblical foundations. He challenged the Church, and specifically the Church of England, to provide moral and spiritual leadership for the nation. Again, such a challenge is long overdue, but it needs to be pointed out that the rôle of the Judaeo–Christian tradition in national life is much more important than the status and rôle of any particular church. Whether or not this or that church provides what the PM is asking for, the tradition must remain central to our public life.

In raising all of these issues, David Cameron has gone further than most political leaders in recent years. Much of what he has said is music to my ears and echoes many of the concerns I have had and have written about in this newspaper..

The proof of the pudding is, however, in the eating and there are a number of challenges which will confront the PM if he tries to give effect in policy and legislation to some of the things he has said in this speech. One issue is that of religious literacy in the Civil Service, Parliament and local authorities. What Cameron has said about the ways in which Christian ideas are embedded in our constitutional arrangements is simply not understood any more in the corridors of power. A disconnected view of history and the fog of multiculturalism have all but erased such memory from official consciousness. A concerted programme is needed if this literacy is to be recovered and used. Theologians, like Philip Blond, and church leaders can help with remedial action but, in the end, this has to do with the place of the Bible and Christianity in the schools. Nor is this only about school assembly and Religious Education (important as they are) but also, for example, with the teaching of history. Michael Gove has rightly seen that history cannot be just about discrete dates and famous personalities but must be a narrative of the emergence of a people and a nation from the mists of time. For such a project, the place of Christianity is absolutely central. For better or for worse, there would not be a narrative worth the name without taking the influence of Christianity into account. As Cameron has pointed out, values–related education on citizenship, for instance, cannot ignore the fact that many of the values we hold dear, such as responsibility, honesty, trust, compassion, a sense of service, humility and self–sacrifice have demonstrably biblical roots.

I believe that the proper relation of Religion to Science is also vitally important and young people should be enabled to appreciate both the experimental methods of Science and the ultimate values of significance, freedom and destiny which Religion has to offer. Such a conversation must take place in the classroom if we are not to continue being divided by ‘scientistic’ and religious fundamentalists.

In his speech the Prime Minister reminded us that inalienable human dignity is founded on the biblical idea that we are made in the image of God. So far so good but to what or to whom does this extend? How far back in the story of an individual is this dignity to be respected and are there ever any circumstances when a person might lose such dignity? It was for reasons, such as these, that the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act recognised the special nature of the human embryo (where all the genetic material needed for personhood is found) and established an Authority to regulate any scientific or therapeutic work which involved a human embryo. I fully support the Coalition’s desire to deal with the proliferation of Quangos, and the HFEA itself is not perfect by any means. We need, nevertheless, in a fast–changing world, an appropriate body that can consider the moral and social implications of developments in bioethics, as a whole, and advise the government accordingly. The government does not have to accept such advice but not to have it seems to me foolhardy. The Judaeo–Christian tradition will have to play a significant part in any such reflections on bioethical issues. President Bush’s Commission on Bioethics provides one model of how this can be done in an inclusive and non–coercive way, but there are other models available also.

Again, as Cameron reminded us, the value of equality comes from the biblical teaching (now confirmed by science) of the common origin of all human beings whatever their race, colour or ethnicity. It is important to point out that this has to do with the equality of persons and not necessarily with the equal value of all behaviour or relationships. The equality of all before the law is an important development from Judaeo–Christian influence on the law but so is respect for conscience, especially as it is formed by a moral and spiritual tradition such as Christianity. I would hope that legislation initiated by this government will, more and more, respect the consciences of believers. Legislation in the United States, arising from the First Amendment to the Constitution, provides for the ‘reasonable accommodation’ of religious belief at the work place, if such accommodation does not unduly burden other employees or affects the very viability of the employer’s business. It is easy to see that if such a doctrine had been in place in this country we would not have seen the absurd dismissals (and even more absurd judicial decisions that upheld them) of Christians and others because they could not undertake certain tasks on account of their faith. Britain has had a long honourable history of respect for conscience, whether in times of war or in the practice of medicine (where health workers have long been able to opt out of any procedures towards the termination of a pregnancy). The idea of reasonable accommodation could certainly provide further grounds for respecting conscience in matters that are controversial. In a positive meeting with Dominic Grieve, the Attorney General, I was able to discuss ‘reasonable accommodation’ with him and look forward to the idea being reflected in government policy.

The Prime Minister is aware of the vast scale of social service, prison work, development assistance, relief of poverty and the like which churches and their agencies undertake. He is right in expecting their help with the renewal of the big society and his vision of active citizens, involved in their community and working for the common good. Churches and Christian agencies will certainly welcome greater participation in the building up of communities but, at the same time, their integrity must also be respected. They cannot simply be surrogate service–providers for the government. What they say and do springs from their beliefs and the authorities will have to respect these, if there is to be genuine dialogue and collaboration. Let us hope and pray that the Prime Minister’s recognition of the importance of the Bible and of Christianity in public life will provide a springboard for such cooperation and understanding in this New Year.

+Michael Nazir–AliJanuary 2012

Bishop Michael Nazir–Ali is President of Oxtrad, the Oxford Centre for Training, Research, Advocacy and Dialogue, and was the 106th Bishop of Rochester for 15 years, until 2009. Visit his website

here